Home Blog

The Death of King Candaules

When night came, everything was ready for the attack. Gyges knew that there was no way back. He understood that he must either kill...

Gyges Has No Way to Escape

Gyges now found himself trapped. He did not agree with the king’s command, but he could not escape it. He feared the power of...

King Candaules and His Pride

Candaules was the king of Lydia, and he was deeply in love with his wife. He believed that she was the most beautiful woman...

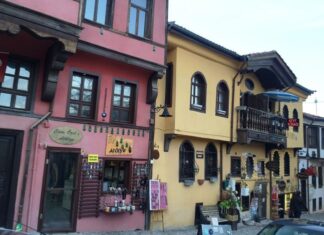

Early Trade and Industry in Bulgaria

Railroads and Urban Specialization

The first railroad in Bulgaria was built in the second half of the 19th century, connecting Russe on the Danube with...

Bulgarias Economy under Turkish Rule

Agrarian Economy and Land Systems

During the five centuries of Turkish rule in Bulgaria (1396–1878), the country maintained a mostly agrarian economy. Farming was the...

Exploitation and the Big Leap Forward

In the late 1950s, the Bulgarian people faced increasing exploitation under the Communist regime. In October 1958, the Bulgarian Communist Party, acting under clear...

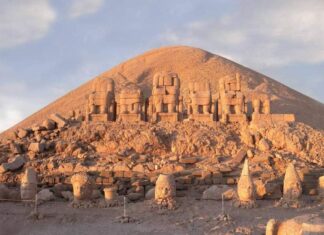

Early Settlement of the Balkans

The Slavs arrived in the Balkan Peninsula from the eastern regions of the Russian steppe during the 5th century. Over the next two and...

Geography and Natural Features

Bulgaria is a mountainous country with a variety of landscapes, including mountain slopes, plains, rivers, and a long coastline along the Black Sea. Its...

Geography of Bulgaria

Location and Borders

Bulgaria is located in southeastern Europe. To the north, it is separated from Romania by the Danube River, which serves as a...

Hermits and Eccentrics of Athens

The Hermit on the Temple of Jupiter

A long time ago, a hermit chose to live on top of the columns of the Temple of...