Ovid (43 B.C.—18 A.D.?)

Publius Ovidius Naso, better known to readers of English as Ovid, was born not far from Rome, and spent the latter part of his life in exile. The Metamorphoses, his most ambitious work, is an attempt to reshape in metrical form the chief stories of Greek mythology, and several from Roman mythology. Orpheus and Eurydice, one of the most human of the legends of antiquity, is a graceful piece of writing. Its “point” is as clear and as cleverly turned as you will find in any ancient tale.

The present translation is based by the editors upon two early versions, the one very literal, the other a paraphrase. The story, which has no title in the original, appears in the Tenth Book of the Metamorphoses.

Orpheus and Eurydice

Thence Hymenaeus, clad in a saffron-colored robe, passed through the unmeasured spaces of the air and directed his course to the region of the Ciconians, and in vain was invoked by the voice of Orpheus. He presented himself, but brought with him neither auspicious words, nor a joyful appearance, nor happy omen. The torch he held hissed with a smoke that brought tears to the eyes, though it was without a flame. The issue was more disastrous than the omen; for the new bride, while strolling over the grass attended by a train of Naiads, was killed by the sting of a serpent on her ankle.

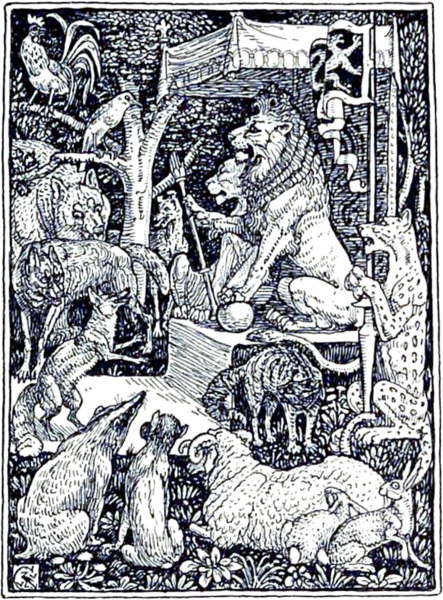

After the Rhodopeian bard had bewailed her in the upper realms, he dared, that he might try the shades below as well, to descend to the Styx by the Taenarian Gate, and amid the phantom inhabitants, he went to Persephone and him who held sway over the dark world. Touching the strings of his harp and speaking, he thus addressed them:

“Oh, ye deities of the world that lies beneath the earth, to which we all come at last, if I be permitted to speak, laying aside the artful expressions of a deceitful tongue, I have not descended hither from curiosity to see dark Tartarus nor to bind the threefold throat of the Medusaean monster bristling with serpents. My wife is the cause of my coming, into whom a serpent which she trod on suffused its poison, and cut short the thread of her years. I wished to be able to endure this, and I will not deny that I have striven to do so.

But love has proved stronger. That god is well-known in the regions above; whether he be so here as well, I am uncertain. Yet I think that even here he is, and if the story of the rape of former days is true, `twas love that brought you two together. By these places filled with terrors, by this vast chaos and by the silence of these boundless realms, I entreat you, weave over again the quickspun thread of the life of Eurydice.

“To you we all belong, and having stayed but a little while above, sooner or later we all hasten to your abode. Hither are we all hastening. This is our last home, and you possess indisputable dominion over the human race. She, too, when in due time she shall have completed her allotted number of years, will be under your sway. The enjoyment of her I entreat as a favor, but if the fates deny me this privilege on behalf of my wife, I have determined that I will never return to earth. Triumph, then, in the death of us both!”

Bloodless spirits

As he spoke and touched the strings of his lyre, the bloodless spirits wept. Tantalus no longer caught at the retreating water; the wheel of Ixion stood still in amazement; the birds ceased to tear at the liver of Tityus, and the granddaughters of Belus paused at their urns. Thou, too, Sisyphus, didst seat thyself on the stone. The story is that then for the first time the cheeks of the Eumenides, overcome by the music of Orpheus, were wet with tears; nor could the royal consort, nor he who ruled the infernal regions endure to deny his request. And they called for Eurydice. She advanced at a slow pace from among the shades newly arrived, for she was lame from her wound.

The RhodOpeian hero received her and at the same time was told the condition that he turn not back his eyes until he had passed the Avernian Valley, lest the grant be revoked. They ascended the path in silence, steep, dark, and enveloped in deepening gloom. Now they were arrived at last at a point not far below the verge of the upper earth. Orpheus, fearing lest Eurydice should fall, and impatient to behold her once again, turned his eyes, and at once she sank back again. Hapless woman, stretching out her hands and struggling for the arms of her lover, she caught nothing but empty air. Dying a second time, she complained not of her husband, for why should she complain of being beloved? Then she pronounced the last farewell, which he scarcely heard, and again was she hurried back whence she had come.

And Orpheus was astounded and perplexed by this two-fold death of his wife.

Read More about The Soul of Veere Part 1