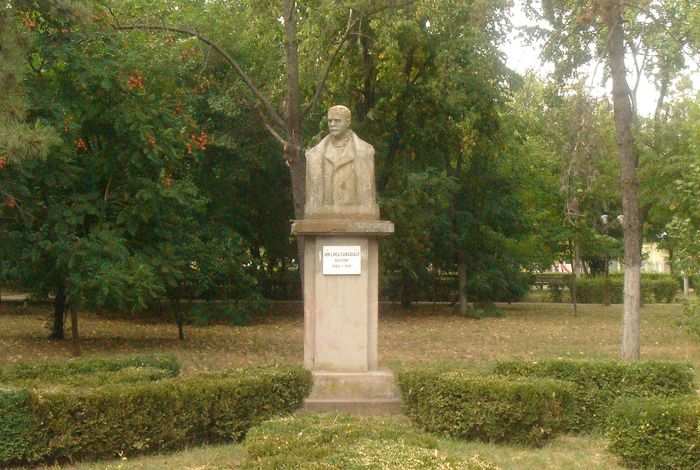

Easter Torch – Ion Luca Caragiale (1852 —1912)

Caragiale first came to the attention of his country’s readers through the pages of Convorbiri Literare, a] literary periodical to which he contributed several short stories. Maiorescu, Roumania’s most distinguished critic, became at once interested in this new author, and under his influence, Caragiale quickly assumed a place of importance among the writers of his country. Prof. S. Mehedintzi, in a preface to Roumanian Stories, writes: “Caragiale, our most noted dramatic author, is … a man of culture, literary and artistic in the highest sense of the word. The Easter Torch ranks him high among the great short-story writers.”

This story, translated by Lucy Byng, appeared in Roumanian Stories, published in 1921 by John Lane, by whose permission, and that of the translator, it is here reprinted.

The Easter Torch

Leiba Zibal, mine host of Podeni, was sitting, lost in thought, fey a table placed in the shadow in front of the inn; he was awaiting the arrival of the coach which should have come some time ago; it was already an hour behind time.

The story of Zibal’s life is a long and cheerless one: when he is taken with one of his feverish attacks it is a diversion for him to analyze one by one the most important events in that life.

Easter Torch – Huckster, seller of hardware, jobber, between whiles even rougher work perhaps, seller of old clothes, then tailor, and bootblack in a dingy alley in Jassy; all this had happened to him since the accident whereby he lost his situation as office boy in a big wine-shop. Two porters were carrying a barrel down to a cellar under the supervision of the lad Zibal. A difference arose between them as to the division of their earnings. One of them seized a piece of wood that lay at hand and struck his comrade on the forehead, who fell to the ground covered in blood. At the sight of the wild deed the boy gave a cry of alarm, but the wretch hurried through the yard, and in passing gave the lad a blow. Zibal fell to the ground fainting with fear. After several months in bed he returned to his master, only to find his place filled up. Then began a hard struggle for existence, which increased in difficulty after his marriage with Sura. Their hard lot was borne with patience. Sura’s brother, the innkeeper of Podeni, died; the inn passed into Zibal’s hands, and he carried on the business on his own account.

Here he had been for the last five years. He had saved a good bit of money and collected good wine—a commodity that will always be worth good money. Leiba had escaped from poverty, but they were all three sickly, himself, his wife, and his child, all victims of malaria, and men are rough and quarrelsome in Podeni—slanderous, scoffers, revilers, accused of vitriol throwing. And the threats! A threat is very terrible to a character that bends easily beneath every blow. The thought of a threat worked more upon Leiba’s nerves than did his attacks of fever.