Venezuela

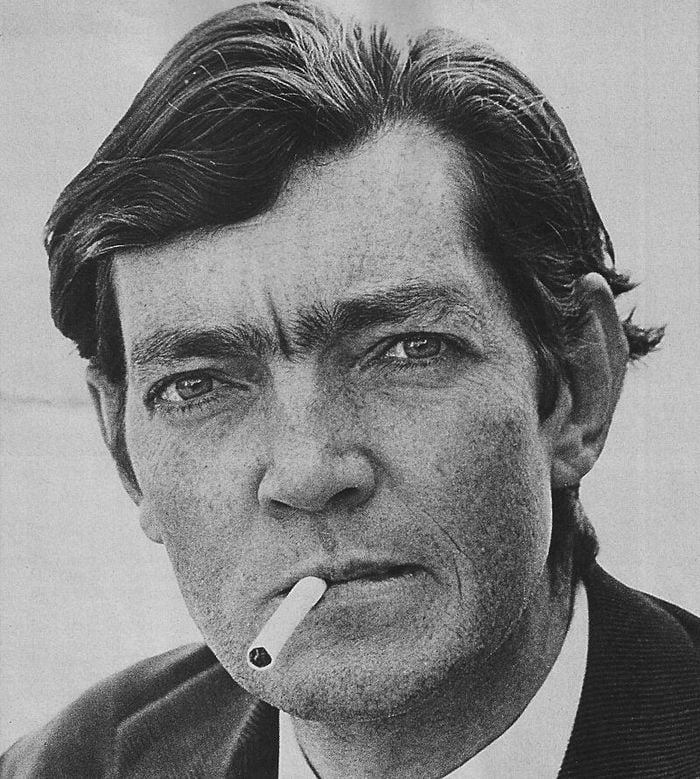

Rufino Blanco-Fombona (1874-1944)

Blanco-Fombona was born at Caracas, in Venezuela, in 1874. He came of an old and aristocratic family of Spanish descent. His extraordinary activities, not only as a writer, but as politician, revolutionary soldier, and government employee, together with his picturesque personal exploits, all contributed to make him one of the most interesting figures in Spanish-America. He travelled in many parts of the world. His writings include criticism, poetry, political essays, novels, and short stories, the first collection of which appeared in 1900. Of Creole Democracy, perhaps his finest short story, Dr. Goldberg has said that “not many tales that have come out of South America can match it.”

The present version, revised from an earlier version, is here printed by permission of the translator, Isaac Goldberg.

Creole Democracy

The hamlet of Camoruco stands at one of the gateways to the Plains The wagon-road cuts the little settlement squarely and neatly in two, like the parting of a dandy`s hair. Stretched out upon the savanna, the village consists of two rows of houses which stand in a file along the edge of the road, and seem to peer furtively upon the passer-by. They look like a double row of sparrows upon two parallel telegraph wires. Close by flows the Gurico, an abundant stream that irrigates the pampas; in its sands slumbers the skate-fish and on its banks, with halfopen jaws, the lazy alligators take their noonday rest.

It was election time; a governor of the Department was to be chosen. For certain political reasons the interest of an appreciable part of the Republic was centered upon the contest. El Faro (The Lighthouse), a backwoods sheet which had been established for the occasion, declared its opening number: “Perhaps for the first time in Camoruco, the elections will cease to be the work of a group of petty politicians, mere vote- manufacturers; perhaps for the first time in Camoruco the elective fabric will be woven by the unsullied hands of the people.”

The number of candidates had dwindled to two. On the eve of the election the local bosses, wealthy cattle-breeders of the district, brought into the neighboring town, which served as a business center for the shacks of the outlying settlements, herds of peons, submissive farm hands, good, simple plainsmen, ignorant of everything, even of what they were to do in the next day`s election; for these peons, rounded up like cattle, were the citizens, that is to say, the voters. The apparel of most of them consisted of drill trousers and striped shirts; on their feet, hempen sandals; on their heads, the high-crowned, wide-brimmed sombrero, or the saffron-colored pelo de guama; around their waists, slung diagonally like a baldric, the red and blue sash; in their right hands, like a cane, they carried the peasant weapon, the ever-present machete.

Read More about The Robbers of Egypt