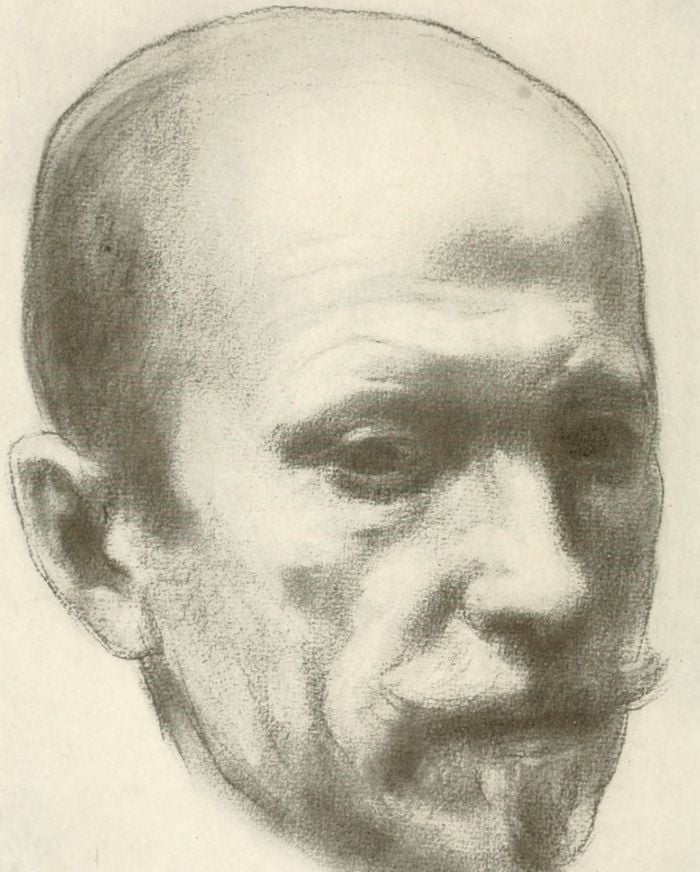

Johan Bojer (1872—1959)

Born at Orkedalsovan, Bojer spent much of his early life in the rural districts of his country. He became interested in politics as a young man, and his first book was a satirical work with a political background. His most significant works (though he also wrote a few plays) are his novels and tales. Among the former the best known are The Great Hunger And The Power of A Lie. He travelled widely.

His short story, Skobelef translated by Sigurd B. Hustvedt, appeared originally in the American-Scandinavian Review, July, 1922, and is here reprinted by permission of the editor.

Skobelef

Skobelef was a horse.

This was in the days when the church bells of a Sunday morning sent out their summons, not over moribund highways and slumberous farmsteads, but over a parish waiting to be wakened into life by the sustained, solemn calling of those brazen tongues. The bells rang, rang, till the welkin rang again:

Come, come,

Old and young,

Old and young,

Rich man, poor man,

Dalesman, fisherman, man from the hills,

The forest, the fields,

The strand, the fells,

Mads from Fallin, and Anders from Berg,

And Ola from Rein,

And Mette from Naust,

And Mari and Kari from Densta-lea,

Lea, lea,

Come, come,

Come, come,

Come.

And so the roads grew black with people on their way to church, some walking and some riding. Old codgers wheezed past, stick in one hand, hat in the other, their coats under their arms, and their gray homespun trousers tucked into boots shiny with grease. The women trundled along carrying shawls and hymn-books, and scenting the breeze with their perfumed handkerchiefs.

Out on the lake, bordered with hills and farms, appeared row-boats driven over the water by sturdy oarsmen; from across the fjord swept the sail-boats; far up in the mountains it seemed as if the cattle even stopped grazing; and the boy who was watching them put the- goat-horn to his lips and blew a stout blast down toward the folks at home. In those times Sunday was both holy day and holiday.

Looking back after these many years, I have a vivid impression that all the world was sunshine and green forests on a day like that. The old church, brown with tar, standing amidst the crowns of mighty trees, seemed then to be more than just a building; there was something supernatural about it, as if it knew all there was to be known. Many hundreds of years had passed over it. It had seen the dead when they were still alive, when they went to church like ourselves.

The surrounding graveyard was a little village of wooden crosses and stone slabs; and the grass grew wild between the leaning monuments. We knew well enough that the sexton mowed it and fed it to his cows; so that when we got a drink of milk at his house we felt as if we were quaffing the very souls of the departed, a kind of angelic milk from which we drew transcendental virtues with every draft.

Read More about Creole Democracy part 1